This was one of those weeks I just didn’t feel like cooking. I especially didn’t feel like wading through old health-food books and suffering through some millet/barley/lentil/sunflower seed concoction night after night. I love that type of food, but I don’t love that type of food all the time.

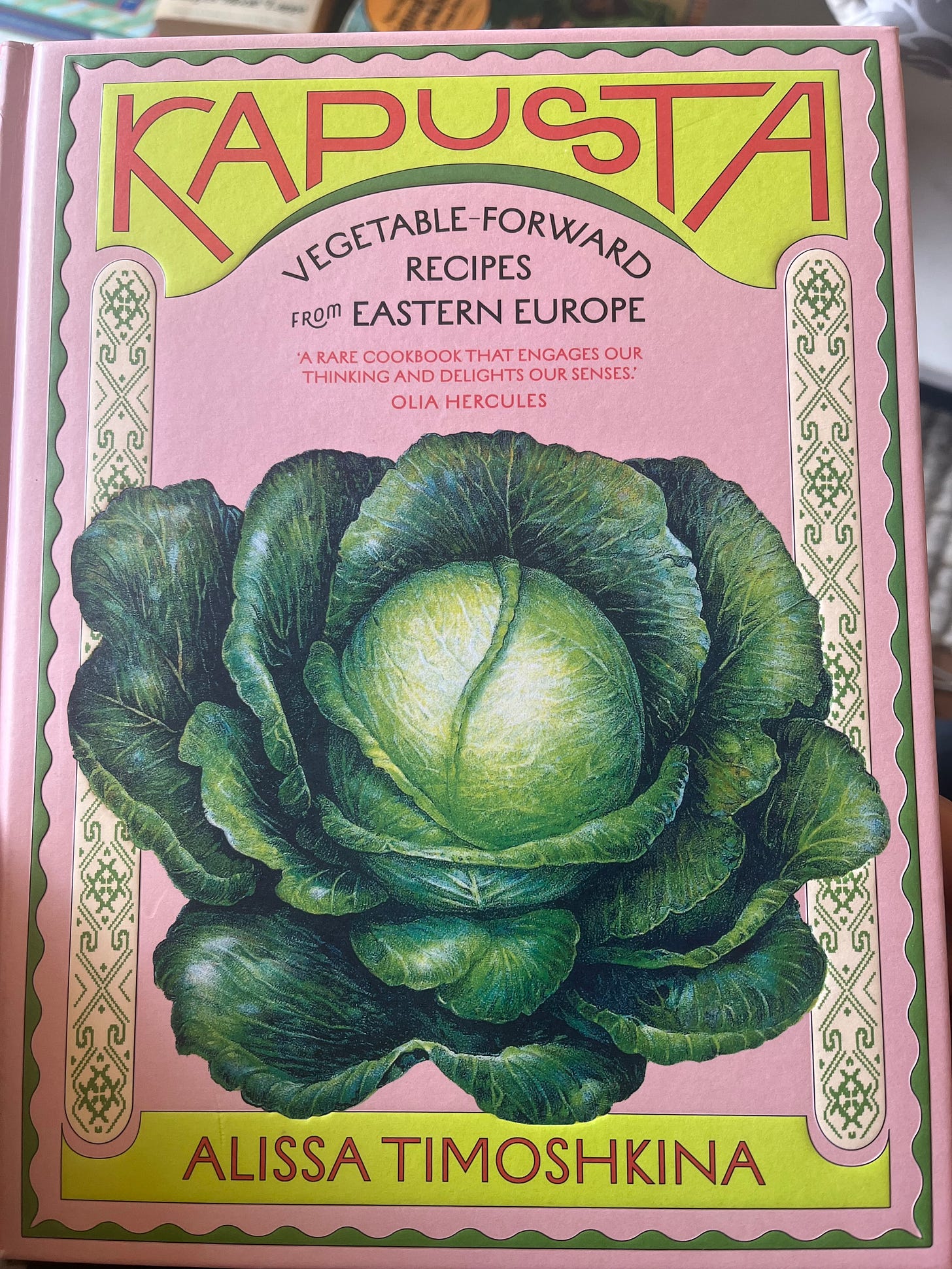

I randomly received Alissa Timoshkina’s new Eastern European “vegetable-forward” cookbook Kapusta in the mail after entering a giveaway on Maggie Hoffman’s The Dinner Plan Substack. By the way, if you’re looking for a relaxing pod to listen to while you cook, The Dinner Plan is the best. Hoffman is an alum of Epicurious and Serious Eats, and she knows everyone in the food world. Chefs aren’t always able to verbally articulate their processes, but Hoffman has the ability to get them to open up, get in the weeds, and really talk. For someone so new to the podcasting game, she’s a natural.

So far on this newsletter, I haven’t written much about contemporary trends in vegetarian and health-food cookbook writing. It’s obviously harder to write from a historical perspective about the present, and we’ll have to be a bit more removed from the moment before those trends are clarified. Anecdotally, the one throughline I’ve noticed over and over again in cookbooks from the late ‘10s and early ‘20s is (especially for books from authors who don’t work for a legacy publication or have a huge online audience) the necessity of a personal, historical, and ethnic connection to the food they’re cooking.

I don’t want to put a value judgment on these new rules of rigidity, about who has the right to be an authority about which types of food. “Authority” is a loaded term, intertwined with historical and systemic racism, classism and misogyny. The story of food, like the story of history, has always been told by the colonizers, the conquerors, the anthropological observers rather than the cultural participants. When I was growing up, if you wanted to learn how to cook Mexican food from English language cookbooks, there were two authors you turned to: Diana Kennedy and Rick Bayless. They are, without question, knowledgeable about Mexican cuisine, and their cookbooks are beautifully written and rigorously researched. But it’s totally insane that there were no contemporaneous Mexican chefs or recipe developers given access and permission to be an equivalent authority on Mexican food.

Now, things, at least when it comes to cookbooks released by the major publishers, have pivoted. Cookbook authors are encouraged (required?) to develop recipes connected to their own history and heritage. This allows for a variety of voices, once marginalized, to speak. Timoshkina, according to her “about the author” blurb, was born in Siberia and has Ukrainian-Jewish, Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, and Belarusian heritage. No one is better suited to write an authoritative cookbook on Eastern European cuisine.

According to my 23andme results (don’t worry, I deleted my data), I’m also mostly Eastern-European. 60.5% Ashkenazi Jewish, to be exact. My mother’s mother’s grandparents came over in the late 19th century from Austria-Hungary (everywhere from Vienna to Hungary to what is now Romania). My mother’s father’s parents emigrated later, around 1910, from Russia, according to the vague information available on familysearch.org (thank you Mormons!) Someone attached an immigration record to my great-grandfather claiming he came to Ellis Island in 1910 from “Nowogorodok,” now Navahrudak, Belarus, close to the Lithuanian and Polish borders. I have no idea if this is true, though according to Wikipedia, Navahrudak’s population was half Jewish before World War II, so it’s possible.

I don’t need to go down a genealogy wormhole, though, fun fact, the (extremely non-Jewish) Peter Rucker arrived in Virginia from Alsace-Lorraine in 1700, and his son soon purchased land for the family in Spotsylvania County. I’d rather not learn more about my Virginian ancestors, who owned people as well as land.

Regardless of any pride or shame in my heritage, it clearly doesn’t afford me any authority to cook Eastern European Jewish food or Southern American food. My mom is a couple of generations removed from the shtetl. My dad was a couple of centuries removed from the plantation. I’m a fourth-generation Californian and much more comfortable cooking lentil loaf, artichoke pizza, and chile rellenos.

I’d long wanted to learn more about my Jewish heritage, even to express some pride in my Jewishness, even though I was never bar mitzvahed and don’t know a word of Hebrew. But now, to be quite honest, I feel much more ambivalent. The genocide of the Palestinian people is ongoing by a people and a state who claim to be protecting Jews. This Tuesday, film director Hamdan Ballal (who won an Oscar only a few weeks ago) was assaulted and almost killed by people who claim to be protecting Jews. Producer Marc Platt, mouthpiece for a multibillion-dollar company founded by an accused anti-semite, publicly blamed the failure of his artistically empty Snow White remake on a young actress who tweeted “and always remember, free palestine.” Platt’s son, who hosts a podcast called “Being Jewish” (haven’t listened to it), accused her of “narcissism” and admonished her for “dragging her personal politics into the middle of promoting a movie.” Calling for the emancipation of Palestinian people is narcissistic? Calling for the end of a genocide is personal politics? These are sick and evil people, and I don’t want to have anything to do with them.

To add insult to injury, I burned my fritters. I blame no one (not even Netanyahu) but myself, though I will give a slight side-eye to Timoshkina, who directs us to fry the fritters on medium-high for four minutes per side. Maybe my cast-iron pan got too hot. I probably should have used the non-stick since these fritters are more pancake than latke.

Interestingly, when Timoshkina shared the recipe to her Instagram, she revised “fry on each side on a medium high heat for 4 minutes” to “fry on each side for four minutes,” so I might have not been the only burn victim.

Timoshkina explains that these fritters (known as syrniki in Slavic), are made of grated carrots fried in honey, raisins, flour, eggs, and an Eastern European sweetened cottage cheese called “twarog.” She goes on to reference Jewish food historian Leah Koenig, who traces the cottage cheese fritters entering Eastern Europe via Italian Jews, who made a similar pancake made with ricotta. So, because Trader Joe’s doesn’t yet sell tubs of organic twarog for $3.99, I (in honor of my supposed medieval Italian ancestors) also used ricotta.

A little powdered sugar and crème fraîche (in honor of my Alsatian great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather Peter) can save just about anything. And these, despite the slight char, are delicious — a cross between lemon ricotta pancakes and carrot cake.

When I’m back in a cooking mood, I’ll be excited to make other recipes from Kapusta. The Mushroom and Rice Stuffed Peppers in Sour Cream (I love a stuffed pepper) sound especially enticing. But will these recipes make me feel closer to my ancestors? Can my eating cabbage and mushrooms and potatoes honor my great (and great-great) grandparents who became refugees when their countries decided they were less than human, expendable, not worth protecting from those who wanted them dead? Food is powerful, but it doesn’t make miracles.

THIS is beautifully and creatively written! Great commentary all around.

And thanks for my and Dad's familial history lesson (had to look up what a shtetl even is!). 😏😅